Updated Sept. 15, 2020, see note at end

This week’s “The Big Story” episode is a “journalism procedural” about a Richmond News Leader reporter who takes up the case of a man convicted of murder six years earlier. Exactly when the original news stories appeared and the real names of people involved were never mentioned in this series, but I suspect this one goes back to the 1930s or earlier. Unfortunately, the News Leader is no more, and the two Virginia universities near me don’t have it on microfilm.

It was common practice for Big Story cast members to voice more than one role in an episode, as in this case.

Like the reporter in the based-on-a-true-story movie “Call Northside 777,” Julian C. Houseman, real-life reporter and star of this episode stubbornly tracks down witnesses, interviews people on both sides of the case, and convinces the prisoner — called “Jamie Goodwin” in the script — that his freedom is worth fighting for.

The episode title, “The Bitterest Man On the Earth,” suggests that the prisoner had all but given up hope.

His original defense attorney is not a character in the play — in fact, the reporter appears to be the man’s sole advocate. As in other “Big Story” scripts, that may be a simplification to add to the drama and fit the time limit, but it also might serve to enhance the audience’s esteem for the power of the press.

The state’s attorney believes the testimony of the murdered woman’s mother and a friend, both adamant that the prisoner is the man who married and then killed the victim.

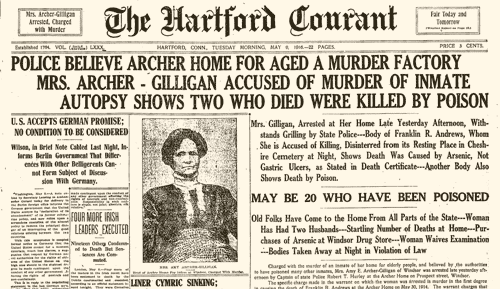

Broadcast as a “The Big Story” episode June 8, 1949 and presumably actually taking place much earlier, the case pre-dates DNA testing, ubiquitous photo-IDs, computerized records and CSI techniques we’ve come to expect in crime dramas, and in real-life.

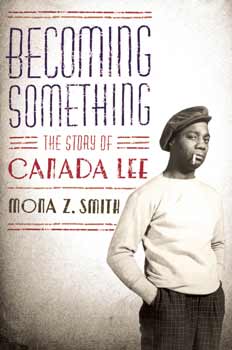

John Sylvester played the part of Houseman, while Canada Lee was the convict. In the television version of the episode, broadcast Nov. 25, 1949, the convict was played by Frank Silvera, according to the TV.com episode guide. (I wonder if Canada Lee was blacklisted on TV between the two performances.)

Even the prisoner’s father admits that the man looks like his son. Neither race nor racial profiling is ever mentioned, although the actors’ accents show that medium that gave us “Amos and Andy” was hardly color-blind. As J. Fred MacDonald notes (in Don’t Touch That Dial), African-American actors found few serious dramatic roles on radio. This episode of “The Big Story” is one case where they did.

While some of radio’s regional, ethnic and racial accents were parodies and terrible stereotypes, the cast members of this episode play it straight, serious and well — despite scripted attempts at dialect that might have gone badly with less talented actors.

Mister, go won away. Who cares ef a backwoods boy like me live or die? Go won away — leave me be. — Jamie Goodwin, from the archived script

The episode script is available in PDF photo images of the broadcast scripts at the Old Time Radio Researchers, where this is Big Story program number 115.

Among the cast members identified in the script is one who appeared in another 1930s series I’ve discussed here. Broadway and film actress Georgia Burke, who voiced two roles in this episode, played a more stereotyped role in the long-running soap opera “Betty and Bob,” Magnolia, the newspaper-owning couple’s maid.

The “Big Story” script says the murdered woman’s friend, “Bertha,” was played by “Pauline Meyers,” a variant spelling for Paulene Myers, a black actress whose stage, film, radio and TV career spanned 54 years. (While she wasn’t a regular in any journalist radio series, she did make an appearance in an episode of TV’s Kolchak, facing another kind of investigative reporter.)

While the script does not say race was an issue in the “Goodwin” trial, it’s clear from the start the program is affirming the fact that a black man can get a fair trial in America — at least with help from a crusading newspaper reporter. The program opens to music and voices a Harlem dance club, a scene followed by the announcer’s voice-over that Houseman is receiving his Pall Mall Award, “for his contribution not only in writing a great story, but in reaffirming a great truth, that every person on Earth is a human being and has a right to human dignity.”

Houseman’s newspaper, The Richmond News Leader, which published from 1888 to 1992, had a reputation for an editorial stance that was conservative and, around the time of this story, pro-segregation, even after the Supreme Court school desegregation decision of 1954.

In the close of the program, Houseman’s telegram accepting the $500 “award” for the story, as given in the broadcast script, said:

“Day after trial Goodwin visited the paper and said, ‘I just wanted to come to the people who got me out of this jam… I needed assistance and it’s the News-Leader that I owe my freedom.'”

Note: I still hope to track down the original newspaper stories — about the murder, the retrial and, if there were any Virginia stories about it, this broadcast — and add to this essay in the future. Tips and suggestions? Add a comment or write to me.

Update 2020: Radio historian Joseph Webb has tracked down original Big Story news sources for his project “The Stories Behind The Big Story” — and found the 1932 murder and 1938 retrial and release of the mistaken-identity convict. See his reporting here, “Episode #115 1949-06-08 “Bitterest Man on the Earth,” Julian C. Hauseman, Richmond News Leader.”

More research on the Richmond reporter’s career might prove interesting. First step in identifying him: Getting his name right! Was it Julian Hauseman, Houseman, or Housman? I’ve seen all three spellings in old-time-radio articles about the Big Story episode. “Houseman” is the spelling in the episode script as republished at the Generic Radio Workshop Script Library.