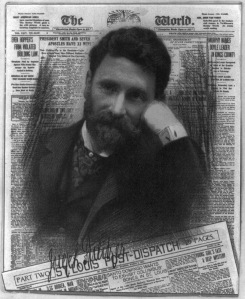

Publisher Joseph Pulitzer — of the New York World and St. Louis Post-Dispatch — was born on April 10 (in 1847), which is as good an excuse as any to offer two versions of his biography as presented to radio listeners of the 1930s and 1940s.

Publisher Joseph Pulitzer — of the New York World and St. Louis Post-Dispatch — was born on April 10 (in 1847), which is as good an excuse as any to offer two versions of his biography as presented to radio listeners of the 1930s and 1940s.

While radio was the “new medium” until TV and the Web came along, I’ve found few radio dramas that cast negative images on the old-time newspaper business. These all-positive biographies of Pulitzer are no surprise. In the 15 or 30-minute format, it would have been hard not to tell an upbeat story about an enterprising immigrant who became a national leader, despite failing eyesight, and who left a legacy as a great philanthropist, endowing both a major journalism school and America’s top prizes for newspapers and literature.

A 1930s Canadian-produced series called “Captains of Industry” profiled Pulitzer in its third episode, after industrialists Andrew Carnegie and George Westinghouse. It picked up Pulitzer’s life story in 1868 in St. Louis, working on a German language newspaper and pledging to improve his English. It concluded with his drafting of the will that endowed the Columbia University journalism school and the Pulitzer Prizes, not long before his death in 1911.

“This is a land of opportunity, and Joey Pulitzer has the nose of an opportunist,” one of his new employers observes, early in the 15-minute episode — which is more about Pulitzer the entrepreneur and philanthropist than his policies, papers or crusades as a journalist.

(For more about the series, see the Captains of Industry page at radio history site Digital Deli Too.)

For a brief account of Pulitzer’s life, but still more complete than either of these dramatizations, see the biography page at Pulitzer.org

The DuPont Cavalcade of America historical drama series cast an accent-free John Hodiak as the Hungarian-born newspaperman in its May 12, 1947, half-hour episode titled “Page One.”

The always patriotic and uplifting DuPont program began with Pulitzer’s experience as an immigrant who fought in America’s Civil War and then “walked the streets with other discharged soldiers looking for a job.” Seven minutes into the story, his editor describes him as “demon reporter, the boy wonder…” He studies law while working at the newspaper, falls in love, and abandons his idea of a law practice when he stumbles on the auction of the St. Louis Dispatch.

“Just another paper gone broke,” a friend says, but Pulitzer bids $2,500 — apparently on impulse.

“I’ve bought responsibility, and a duty to the people,” he says. “Very well, I’ll make it the best newspaper I can.”The same crusading spirit carries to his purchase of the New York World, and to his dramatic crusade to raise funds for the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1884, the main dramatic scene of the broadcast.

“The people. The people. It’s their country, their liberty,” he says.

In both the Captains and Cavalcade series, Pulitzer failing eyesight is a major part of the story, along with Pulitzer’s endowment for Columbia and the prizes that bear his name. The Cavalcade episode has more to say about journalism and public service than the earlier broadcast.

However, I’ll have to give each program a fresh listen. If my memory is right, neither one even mentions the name of William Randolph Hearst or the sensational “Yellow Journalism” circulation war between Pulitzer’s World and Hearst’s Journal around the time of the Spanish American War. (If you know of an old-time-radio program dramatizing that tale, or Hearst’s biography in general, please let me know!)

Hearst, unlike Pulitzer, lived through the years in which radio drama flourished. He died in 1951. His company got into the radio business early, as well as newsreels and television. He took to the air with editorials, and a radio series called “Front Page Drama” featured stories from American Weekly, a magazine distributed with all Hearst Sunday newspapers. But, so far, I’ve found no evidence of anyone using radio to attempt to tell Hearst’s life story. For more about him, see this biography page at Hearst Castle. And, of course, Hearst had his major encounter with “dramatization” in another medium — when radio-star Orson Welles went to Hollywood to produce Citizen Kane, with many echoes of Hearst’s life. Perhaps the broadcast media had a post-Kane “hands off” policy about risking Hearst wrath? (For more on Kane and Hearst, see this PBS American Experience documentary.)

Back to Pulitzer, I’ll also have to listen closely to hear whether religion ever enters into the story. (See the Pulitzer.org website for some discussion of young Pulitzer being taunted as “Joey the Jew,” and the older publisher being attacked by a competing paper for not being more Jewish.)

The Cavalcade episode ends with Hodiak reading “Pulitzer’s creed,” to applause from the live studio audience:

“Our republic and its press will rise or fall together. Only an able, disinterested public-spirited press with a trained intelligence to know the right — and the courage to do it — can preserve that public virtue without which popular government is a sham and a mockery.”

A new book about cartoonist

A new book about cartoonist