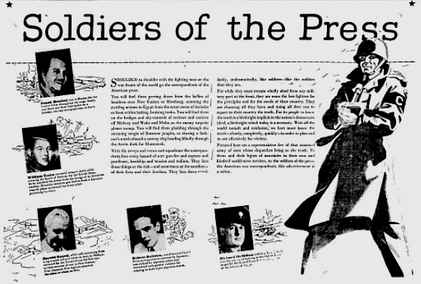

William Tyree was already in Hawaii as a United Press reporter when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. In this “Soldiers of the Press” episode a year later, he recalls being talked out of his first impulse after the attack — to quit the wire service and enlist in the military. Instead, he became one of U.P.’s most experienced correspondents covering the war in the Pacific. Google’s news archive, much of it drawn from smaller papers that relied heavily on United Press, includes many stories with Tyree’s byline and Pacific datelines.

William Tyree was already in Hawaii as a United Press reporter when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. In this “Soldiers of the Press” episode a year later, he recalls being talked out of his first impulse after the attack — to quit the wire service and enlist in the military. Instead, he became one of U.P.’s most experienced correspondents covering the war in the Pacific. Google’s news archive, much of it drawn from smaller papers that relied heavily on United Press, includes many stories with Tyree’s byline and Pacific datelines.

The 15-minute radio drama includes his editor’s advice at the start of it all — that in the Army he would just be “a passable buck private,” while as a war correspondent he would be able to put his six years of training and experience to work.

“You’re a trained man working on a job that it vitally important to the war effort, gathering the news, getting it right, and getting it out.” –Tyree’s editor

The dramatization includes several examples of the World War II correspondent’s identification with the war effort, from Tyree’s constant use of “we” to describe the U.S. forces (and “Nips” to describe the Japanese) to his remark that, “I cheered with the crew when the skipper announced the score over the ship’s public address system.”

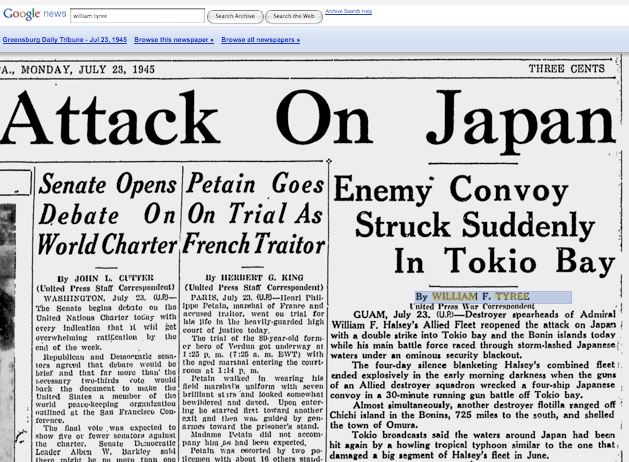

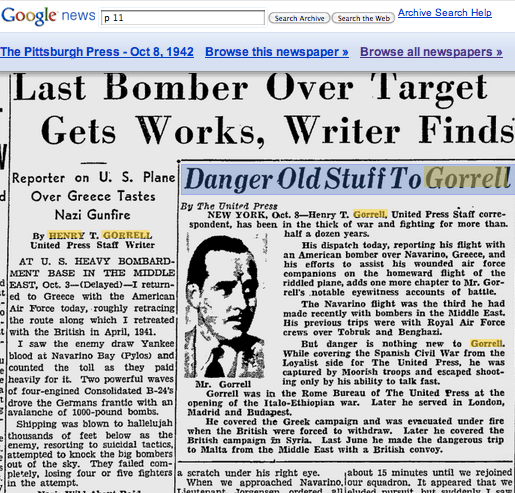

The clip above from July 1942 (click through for full text) describes some of his experiences aboard ship during the Battle of Midway, which is also mentioned in the autobiographical broadcast. (He wrote more about Midway as a turning point in the war in a 1944 United Press retrospective story.)

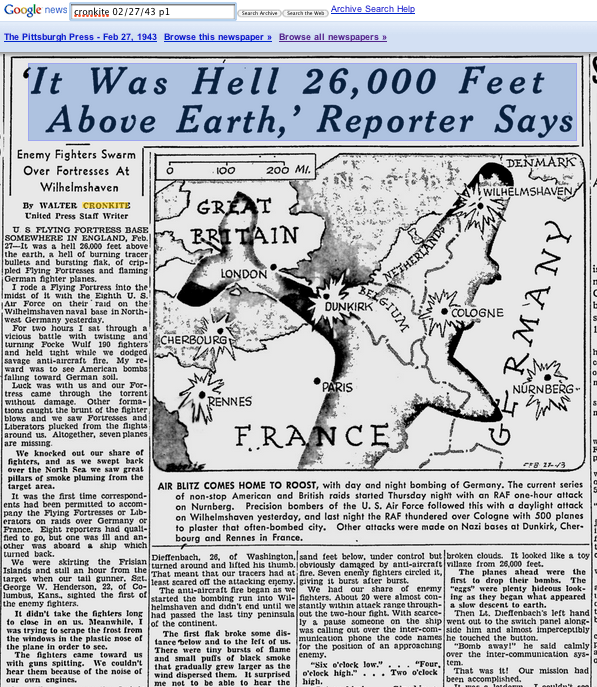

Long before the word “embedded” was used to describe a war correspondent’s role, Tyree saw action aboard battleships and bombers from Pearl Harbor to the Coral Sea, Midway, Guadalcanal and on to the bombings of Tokyo and Hiroshima. In the “Soldiers of the Press” episode, he describes several “too close for comfort” times when his life was at risk.

On Guadalcanal, he meets up with another U.P. man, Francis McCarthy, oblivious to broken ribs suffered on patrol with the Marines. They discuss breakfast while bombs explode around them, and they joke about Japanese snipers who can “knock the ashes off your cigarette at 200 yards.” “Sounds just lovely,” Tyree says. He continued to report on the war in the Pacific through its end.

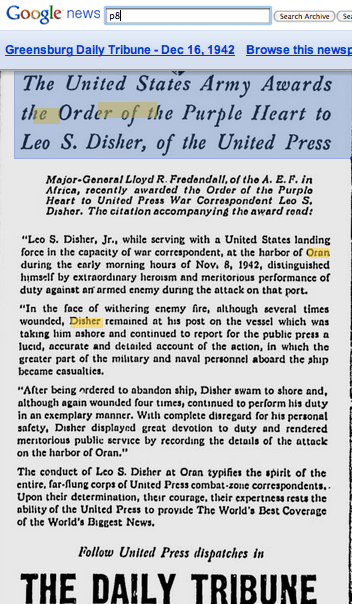

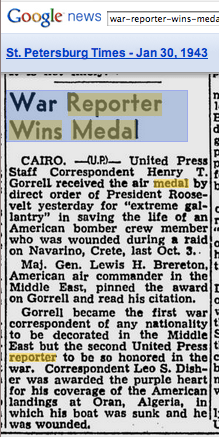

As with all “Soldiers of the Press” broadcasts, actors took the roles of the real war correspondents, soldiers, sailors and military officers. The series was both a dramatic form of public service reporting and a self-promotional effort by United Press, a smaller service that competed with the Associated Press for newspaper and broadcast news subscribers. (See previous JHeroes items from World War II, or the JHeroes.com “Soldiers of the Press” page and links on that page.

In 2009 what is now United Press International, a much scaled-down service, reprinted Tyree’s story about the bombing of Hiroshimaon its website. Tyree stayed with United Press after the war, working in Los Angeles and Oregon, where he was radio editor. He later became Los Angeles manager of United Press Movietone-Television and died in 1960 at the age of 46, according to his New York Times obituary.

For additional information about “Soldiers of the Press,” see the Digital Deli Too logs and discussion of the series. About 40 of the 140 or more broadcasts are available online at the Internet Archive, through the Old Time Radio Researchers Group Soldiers of the Press collection.