In the 1940s Superman did his part as a commercial spokesman at Christmas, while not-that-mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent fought crime on the radio.

December 1946 — The bad guy in this Superman story isn’t threatening the world, but he could cost Clark Kent his job, and right before Christmas too!

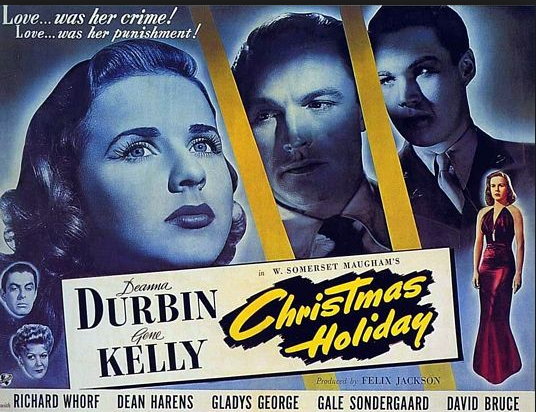

Yes, as the headline above suggests, the villain is a racketeer named Nielsen, but not to be confused with the outfit that introduced a new high-tech “audimeter” that year for rating the popularity of radio programs.

The evil doer’s name may have been a coincidence, or a radio-writer’s in-joke — presumably flying well over the heads of the youthful listeners to Mutual Broadcasting System’s daily “Adventures of Superman” serial.

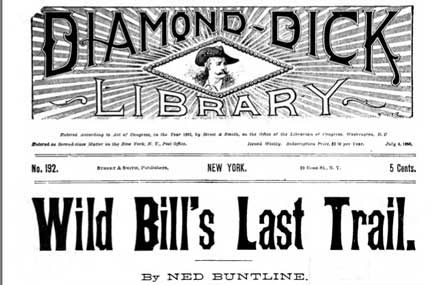

As with many of the Superman radio stories, this one, “The Phony Housing Racket,” has “the power of the press” as hero, not just the super powers of a certain alien visitor. While Superman movies usually have the hero face super-villains who threaten the whole world, from 1940 to 1951 radio’s Superman tales usually were more down-to-earth narratives with social messages aimed at young listeners, and full of reminders that journalism was important.

Here, Clark Kent’s reporter identity is at the center of the action. So are his colleagues at The Daily Planet, especially editor Perry White. Kent’s costumed alter-ego is there for emergency rescues and key cliffhanger moments, but the action revolves around Kent as inquiring-reporter and his boss as a crusading — albeit stubborn, blustering and recklessly over-confident — editor-in-chief.

From episode two of the ten-part serial, White sets out to batter a gang of racketeers with daily headlines warning the public of a real-estate swindle. Kent even urges him to go slow on the expose until his own undercover reporting can identify the mastermind and alert the police. But White presses on. Instead of stopping the racketeers, the Daily Planet’s crusading page-one stories convince the gang leader to silence the paper and intimidate its competition. That turns out to be harder than they expected.

“We’ve thrown the book at Perry White, but he won’t scare. He’s one tough rooster,” a hoodlum tells his boss after a failed attempt to blow up the Planet — the newspaper, not the Earth.

In this two-week story arc, newspaper editor White declares war on racketeers who have been preying on the housing needs of returned World War II veterans. (Only we, the listeners, know that Kent is Superman and that the criminal boss is “square-jawed, immaculately groomed Brock Nielsen.”)

The crooks aren’t fooling around. Before police inspector Henderson tips Kent and White to the mystery of the housing swindles, the gang has already killed one police investigator and one suspicious military veteran. White still insists that racketeers are bluffing cowards. But after the first Planet story, they try telephone threats, then escalate to bombing, kidnapping and extortion.

“Did Nielsen mean death for the dauntless editor?” — cliffhanger ending of Dec. 19, 1946, episode four, as hoods blackjack the gray-haired Perry White in his driveway and carry him off.

Over the weeks of the 15-minute-a-day story, the radio audience got to hear White’s speeches about the paper’s duty to the public, and heard Kent weigh the ethical question of protecting consumers from swindlers versus continuing to risk White’s life.

In a “journalism procedural,” we hear Kent interview a swindled veteran, visit a county clerk’s office to check property records, do some forensic investigating at the scene of Perry White’s kidnapping, and logically deduce that a Daily Planet security guard was framed to cover up the attempted bombing. No super-powers are involved in any of this, just good reporting skills: intelligence, curiosity and powers of observation.

OK, so Kent also goes beyond the average journalism textbook and strays into hard-boiled private-eye territory, like many other dramatic portrayals of reporters, including radio’s “Big Town” and “Casey, Crime Photographer.” In the Christmas Eve episode, Kent tracks down a fake real estate salesman with the help of the whistleblower vet, forces the salesman’s car off the road, disarms him and gives him the third degree before turning him over to the police, narrowing in on the big boss. With White’s life hanging in the balance, Mr. Nielsen gets a more extreme form of Superman third-degree, a bit startling in what was, after all, a children’s show.

The action — and the social messages of “power of the press,” good citizenship, honesty and equal rights — build just in time for Christmas Day and an unabashedly religious message from Superman. Even the hoodlums get second thoughts about what they are doing, with the studio organ softly playing hymns and carols while they reminisce about childhood days when they went to church with their families.

“I bet you robbed the collection plate…” says one.

“Yeah, but not on Christmas Day,” his crony replies.

The story ran from Dec. 16 to 27, 1946, overlapping slightly with two other racket-busting stories, which are also available for downloading on page 11 of the Internet Archive’s extensive collection of old-time radio Superman episodes.

Note: This is the latest in a series of posts and pages about the Adventures of Superman serial and its journalist characters, not all of which are mentioned on the Clark and Lois overview page. Incidentally, an early episode of The Phony Housing Racket mentions that Lois is off “in California.” Perhaps “Lois Lane takes vacation!” should be the real headline of this story.

Another clarifier for infrequent Superman radio listeners: Perry White has an unusual cook named Poco, who speaks only in rhyme. While many radio shows used ethnic-accented houseboys and minority-stereotyped characters for comic relief, Superman had a running post-war anti-Fascist, equal-rights and pro-refugee message, as you will hear in Superman’s Christmas-Day speech in this episode. Poco was strange and comic, but non-ethnic. Like Superman himself, he was a refugee from another planet, which had been destroyed in an earlier episode.

For more discussion of Superman radio show episodes, see the Superman Home Page radio section and the Wikipedia Superman radio page.

The Phony Housing Racket episodes at the Internet Archive can be downloaded from these links or streamed or downloaded with other stories from the archive page. Each program is a little over 3 MB in MP3 format, about 15 minutes of audio including the original cereal-company commercials and promotions.

(Files are listed as date “yrmoda,” overall episode number, and name)…

- 461216-1443 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 01

- 461217-1444 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 02

- 461218-1445 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 03

- 461219-1446 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 04

- 461220-1447 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 05

- 461223-1448 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 06

- 461224-1449 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 07

- 461225-1450 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 08

- 461226-1451 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 09

- 461227-1452 The Phony Housing Racket Pt 10; Phony Restaurant Racket Pt 1